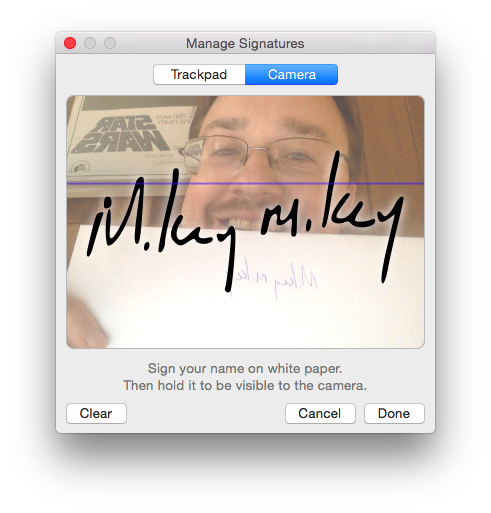

If you’ve never used it before, Preview.app has an amazing ability to pull a signature from the trackpad on your Mac or from the video feed of your FaceTime camera. The feature is located under the menu Tools -> Annotate -> Signature.

The capture experience is pretty magical, second only to (in my opinion) iTunes using your camera to capture your iTunes gift card codes.

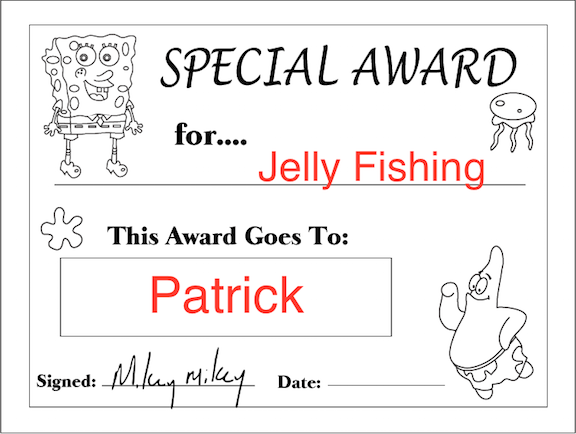

Once it has your signature stored, you can then use the same menu to place your signature into electronic documents like PDFs as transparent image overlays, allowing you to “sign” them.

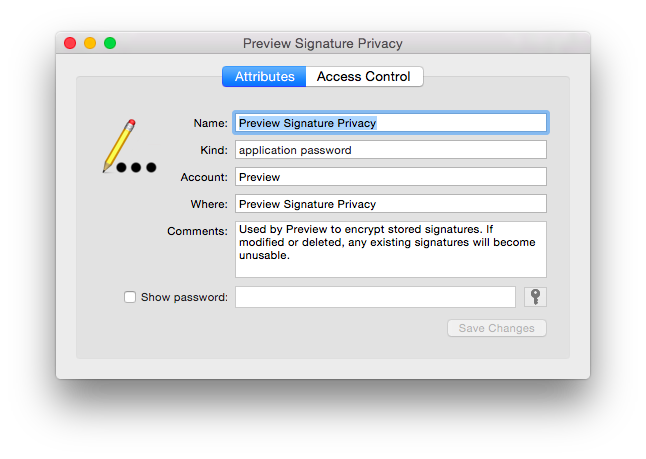

Now that you’ve stored your signature in your computer, one would hope that Apple spent some time protecting others from accessing it.

Fortunately they did.

In OS X 10.9 Mavericks, when you create a signature, two primary pieces of data are configured.

In the user’s login.keychain, an application password keychain item called “Preview Signature Privacy” is created, with the following notes:

* (yes, I know this is a 10.10 screenshot - it’s prettier this way)

The password contents of this keychain item are a hexadecimal string, representing 16 raw bytes of information.

The second item that’s created is an application preference in the domain com.apple.Preview.signatures for the key “items-1”, which contains an array of data objects. The backend storage for this domain is located in the user’s application containers at:

~/Library/Containers/com.apple.Preview/Data/Library/Preferences/com.apple.Preview.signatures.plist

If you didn’t know me already, I’ll just warn you now that my code here will be in python. Since we’re going to be working a lot with plists, let’s get a few helper functions defined.

This has an advantage over the plistlib module included with python in that it can support binary plists as well as just XML.

Next, let’s read the com.apple.Preview.signatures preference for the key “item-1”.

Never. Ever. Read. Preferences. From. Plist. Files. Directly.

(… Unless you want to. I mean, I’m not your dad. Go for it if you really want to. But Apple hates you for it.)

However - following my own advice is a little tricky here! The location of the preference is stored on-disk within ~/Library/Containers, indicating this is a sandboxed application preference and isn’t normally meant to be accessed by other apps outside of Preview.app itself.

… But OS X will still let you read the preference, if you provide the full path to it.

The contents of the array is a data object, which if you try to look at it directly, you just see the hex encoding of it.

But if you look at the first few characters in it, you might see something recognizable:

>>> str(first_sig)[:50]

'bplist00\xd4\x01\x02\x03\x04\x05\x06\x1e\x1fX$versionX$objectsY$archiverT$top'

The first few characters “bplist00” are an indicator that the contents of the array are binary plists themselves. So let’s unpack it.

>>> sig_plist

{

"$archiver" = NSKeyedArchiver;

"$objects" = (

"$null",

{

[...]

Now we’ve got something new - an NSKeyedArchiver object. This is a way for OS X (and iOS) to store data objects in a file-friendly format.

So we need to decode the object. Let’s try!

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

objc.error: NSInvalidUnarchiveOperationException - *** -[NSKeyedUnarchiver decodeObjectForKey:]: cannot decode object of class (PVSignature)

Whoops. Looks like OS X doesn’t know how to natively handle a “PVSignature” file - so where do we learn about it?

We’ll need to compare two different pieces of information: what’s stored in the NSKeyedArchiver object and what exactly is a PVSignature object?

For the PVSignature structure, we’ll need the help of a great tool: class-dump

It can dump the signature of Objective-C objects defined within applications and frameworks (… hopefully PVSignature is within Preview.app itself!)

class-dump -H /Applications/Preview.app/Contents/MacOS/Preview

Yay, our output includes a “PVSignature.h” file.

Let’s see what’s inside:

Now let’s compare that against what’s actually stored in the encoded object.

When storing a single object, NSKeyedArchiver object stores the object attributes in the 2nd item of the “$objects” key:

>>> sig_plist['$objects'][1]

{

"$class" = "<CFKeyedArchiverUID 0x7fd3ada65f80 [0x7fff7951bed0]>{value = 4}";

data = "<CFKeyedArchiverUID 0x7fd3ada98480 [0x7fff7951bed0]>{value = 2}";

uid = 1000;

}

So it looks like we have a “data” and “uid” values only, unlike everything listed above.

Enter my next favorite tool: Hopper (a reverser’s best friend!)

With Hopper, we’ll read the executable to disassemble located at: /Applications/Preview.app/Contents/MacOS/Preview

Once loaded up, we’re going to look under “Labels” for PVSignature initWithCoder (the method that’s called when unarchiving an instance of a class).

Once we find it, we can use Window -> Show Psuedo Code of Procedure

[...]

rbx->_undecryptedData = [[r14 decodeObjectForKey:@"data"] retain];

rbx->_uid = [r14 decodeInt32ForKey:@"uid"];

rbx->_cannotDecrypt = 0x0;

rbx->_shouldPersist = 0x1;

rbx->_largeThumbnail = 0x0;

rbx->_smallThumbnail = 0x0;

rbx->_payload = 0x0;

[...]

Pretty staight forward to immitate:

Yay, no errors! Let’s see what our object looks like:

>>> sig_decoded._uid

1000

>>> sig_decoded._undecryptedData

<458e1def 5434c5ab 94094049 dfd2424d 0ebe7ff6 c79c7b82 463d6d56 ...

Cool. Let’s try the trick we did before for checking out if the raw data is anything we recognize:

>>> str(sig_decoded._undecryptedData)[:50]

'E\x8e\x1d\xefT4\xc5\xab\x94\t@I\xdf\xd2BM\x0e\xbe\x7f\xf6\xc7\x9c{\x82F=mV\xac\xee\x1c\xda8\xe357|\xbb\xa9\xf9\xdc\xbd\x16\x1a+6\x16\x90Z\xfc'

Hmm. Nope. Not ringing any bells.

… It’s like it’s encrypted or something …

But hey, we have that other piece of data - the password value for “Preview Signature Privacy”:

“Used by Preview to encrypt stored signatures. If modified or deleted, any existing signatures will become unusable.”

Sounds like it’s a decryption key to me!

I’m going to cheat here and just raw copy the value using Keychain Access (just clicking on “Show Password” and copying out the value). (I have code for reading from the keychain, but that’s for another post.)

>>> len(binary_key)

16

A 16 byte key. If you know anything about encryption, that’s a pretty common key length for many common block cipher (ECB and CBC) algorithms.

But we need to know exactly what algorithm was used here.

Back to Hopper we go!

Searching through PVSignature code, this would seem key: -[PVSignature decrypt]:

Looking at the pseudocode for it, it generates an instance of a new class “PVSignatureEncryptor”:

rax = [PVSignatureEncryptor sharedInstance];

Based on that, we find: -[PVSignatureEncryptor decryptedData:]:

This code has exactly what we’re looking for - information about how it decrypts the data:

if (CCCrypt(0x1, 0x0, 0x1, r12, 0x10, 0x0, var_68, r14, r15, rax, var_58) == 0x0) {

And in this instance, we want to look at not just the pseudocode, but also the assembly for a little more clarity:

mov edi, 0x1 ; argument "op" for method imp___stubs__CCCrypt

mov esi, 0x0 ; argument "alg" for method imp___stubs__CCCrypt

mov edx, 0x1 ; argument "options" for method imp___stubs__CCCrypt

mov rcx, r12 ; argument "key" for method imp___stubs__CCCrypt

mov r8d, 0x10 ; argument "keyLength" for method imp___stubs__CCCrypt

xor r9d, r9d ; argument "iv" for method imp___stubs__CCCrypt

Looking at the documentation for CCCrypt, we get:

CCCrypt(CCOperation op, CCAlgorithm alg, CCOptions options,

const void *key, size_t keyLength, const void *iv,

const void *dataIn, size_t dataInLength, void *dataOut,

size_t dataOutAvailable, size_t *dataOutMoved);

Now we can figure out the arguments that were passed, with a little help from the CommonCryptor.h header file and the above:

- operation/”op”: 0x1 (kCCDecrypt, from <CommonCryptor.h>)

- algorithm/”alg”: 0x0 (kCCAlgorithmAES128)

- “options”: 0x1 (kCCOptionPKCS7Padding in this context)

- “key” is probably our “binary_key” from above

- “keyLength”: 0x10 which is hex for 16 - a length that matches the length of our “binary_key” 😀

- “iv”: 0, aka null pointer / empty value in this context

The rest of the arguments we don’t care so much about as they’re for handling getting data into/out of the decryption.

With one last bit from the documentation on CCCrypt, we have everything we need:

“If CBC mode is selected and no IV is provided, an IV of all zeroes will be used”

Ok, now to try decrypting. We’re going to use the python Crypto module for this part:

>>> decrypted_data[:50]

"\xe4\x9c\x0f\xff\xd2\xee`\x0e\xbe8w8\xef\xaaT\xf1\x07\xeas\xe0Z\x96'6\xfc\x95\x9e\xa9\xce\xb5>\xd4bplist00\xd4\x01\x02\x03\x04\x05\x06,-X"

Oh ho ho! I see a bplist00 …

>>> decrypted_data.index('bplist00')

32

Looks like there’s a 32 byte prefix - looking back at the code of -[PVSignatureEncryptor decryptedData:], we can see:

CC_SHA256(rbx, rsi, var_50);

SHA-256 is a 32-byte CRC. Likely the decrypted data is prefixed with its CRC hash so that the code can tell easily if it decrypted the signature correctly by validating the hash of the binary plist data matches the hash in the 32 byte prefix.

So let’s skip the first 32 bytes and try to parse it directly as a plist.

… But before we do that, the “kCCOptionPKCS7Padding” option that was mentioned earlier means that this data is padded out to a multiple of 16 bytes:

>>> len(decrypted_data)/16.

120.0

So we have to remove the padding per the PKCS7 standard. We can do that with this bit of code:

Now we can attempt parsing the plist data for bytes 33+

>>> decrypted_plist

{

"$archiver" = NSKeyedArchiver;

"$objects" = (

"$null",

[...]

Success!!

What do we have this time? Let’s try to decode it. But since we decrypted with python, our data is a string - need to wrap it into an NSData object first.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

objc.error: NSInvalidUnarchiveOperationException - *** -[NSKeyedUnarchiver decodeObjectForKey:]: cannot decode object of class (PVSignaturePayload)

Progress - now we’re working with a “PVSignaturePayload”.

Again, let’s look at what data we have, and then compare that against the contents of “PVSignaturePayload.h” from our earlier class-dump run:

>>> decrypted_plist['$objects'][1]

{

"$class" = "<CFKeyedArchiverUID 0x7fba02522bd0 [0x7fff7951bed0]>{value = 7}";

baselineHeight = "0.1176470592617989";

creationDate = "<CFKeyedArchiverUID 0x7fba025203d0 [0x7fff7951bed0]>{value = 4}";

lastUsedDate = "<CFKeyedArchiverUID 0x7fba025203f0 [0x7fff7951bed0]>{value = 6}";

path = "<CFKeyedArchiverUID 0x7fba02520350 [0x7fff7951bed0]>{value = 2}";

}

vs.

Oh goodness - NSBezierPath??

We are SOOOO close.

That’s vector information, very likely our actual signature!

We could look back at the code in Preview.app for PVSignaturePayload - but we appear to have a match for a match on everything, let’s just wing it!

>>> real_sig_decoded.baselineHeight

0.11764705926179886

>>> real_sig_decoded.path

Path <0x7fba0251bb90>

Bounds: {{107.10252904995613, 3.5527136788005009e-15}, {271.91783064182891, 67}}

Control point bounds: {{106.36058807373047, -1.9758532047271729}, {274.53815460205078, 68.975853204727173}}

204.485748 61.750000 moveto

204.099686 58.862499 201.597519 49.750000 198.925385 41.500000 curveto

196.253250 33.250000 193.444489 24.025000 192.683685 21.000000 curveto

[...]

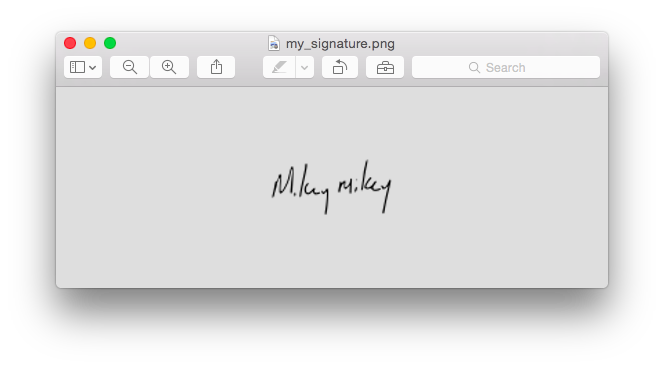

YAY! We’ve got our vector information!

Now, to verify this is what it is, let’s kick it out to an image file.

But NSBezierPath doesn’t have to start at a (0,0) coordinate origin. In fact, the “Bounds” values above indicate it’s offset. So let’s make a transform and shift it back to something more reasonable before we draw it.

>>> sig_path_shifted

Path <0x7fba04ef0000>

Bounds: {{0.10000000000000142, 0.10000000000000001}, {271.91783064182891, 67}}

Control point bounds: {{-0.64194097622566915, -1.8758532047271763}, {274.53815460205078, 68.975853204727173}}

97.483219 61.850000 moveto

97.097157 58.962499 94.594990 49.850000 91.922855 41.600000 curveto

89.250721 33.350000 86.441959 24.125000 85.681156 21.100000 curveto

Much better. Now we’re just inside (0,0).

Now to build an image and draw the path onto it.

(I’m gonna race through this a bit here because we’re so close to the end!)

##veni, vidi, vici!

##final notes

This entire post was about signatures in 10.9.

Signatures in 10.10+ have taken a new turn.

Now the com.apple.Preview.signatures preference domain appears to be legacy: when you upgrade 10.9 to 10.10, OS X appears to perform a one-time conversion of your signatures into the new format. (Speculation on my part - calling Rich, master of OS X VMs, to verify …)

In 10.10+, signatures appear to be stored entirely in the keychain - but not your login.keychain.

Now every signature gets a “Signature Annotation Privacy” item in your “Local Items” keychain (which may be named “iCloud Keychain”, if you’ve enabled that function with your iCloud account).

Instead of an encryption key stored in the password value, an entire binary plist appears to be there.

Additionally, the note has changed:

“Signatures for AnnotationKit (shared by e.g. Sketch & Preview). Deletion will remove all signatures from the list.”

I’ve done some initial investigations into this binary plist value and as expected, the contents are not like they used to be.

I’ll continue looking into it (and maybe write about what I find at some point …)

- mike