Howdy, y’all. Long time 😄

So now the 2018 MacBook Pro exists.

If you didn’t hear, it ships with Secure Boot. If you did hear, you might be freaking out about that.

So I’ve written this blog post for you to read. Mind you, I’m not the only one that’s written about Secure Boot devices.

There are community and tech articles:

- SecureBoot & the 2017 iMac Pro (by the wonderful Tim Perfitt of the excellent Twocanoes)

- Apple iMac Pro and Secure Storage (by the wizardly Pepijn Bruienne)

There are new articles from Apple:

- About Secure Boot

- About Secure Startup Utility

- Mac computers that have the Apple T2 chip

- About encrypted storage on your new Mac

- If your iMac Pro display turns off during startup or updates

- If the fans in your Mac run at full speed when you turn it on

- Apple Configurator 2 Help - Restore iMac Pro (pay attention to this one …)

Even older KB articles got updated.

Some of them are trivia bits:

- Reset NVRAM or PRAM on your Mac

On Mac computers that have the Apple T2 chip, you can release the keys after the Apple logo appears and disappears for the second time. - About Mac startup tones

Mac computers that have the Apple T2 chip don’t have EFI ROM tones. - How to turn your Mac on or off

Additionally, MacBook Pro (2018) turns on when you press any key on the keyboard or press the trackpad.

But more importantly, some of them may have just completely destroyed your entire macOS imaging / provisioning workflows:

- Create a NetBoot, NetInstall, or NetRestore image

Mac computers that have the Apple T2 chip don’t support starting up from network volumes. - Mac startup key combinations

[N key:] Computers that have the Apple T2 chip don’t support this startup key. - How to select a different startup disk

If you’re using a Mac that has the Apple T2 chip, check the settings in Startup Security Utility. These settings determine whether your Mac can start up from another disk.

Your new provisioning reality

What do the changes effectively mean to you - the person(s) responsible for Mac setup workflows?

Secure Boot devices with T2 chips, fresh out of the box:

- Are configured at Full Security mode

- They do not netinstall / netboot. (NetSUS, bsdpy, Server.app’s NetInstall service - none will work)

- You can’t use the N key at startup to boot over the network to an imaging workflow

- You can’t use the Option key at startup to select a network boot target

- They do not boot from external media (USB, Thunderbolt, etc.)

- You can’t use the Option key at startup to select a different attached disk to boot from

Unless your device provisioning/configuration workflow is based on the Device Enrollment Program (DEP), most of you with “light touch” automated provisioning workflows will find they’re now incompatible with T2 devices. (There are a few exceptions, I’ll cover them below.)

If your workflow is based on bootable attached media (since network boot is really dead dead dead), here’s what you have to go through to enable this:

- Make sure the external boot media you created will even boot the device (the 2018 MacBook Pro runs a custom 10.13.6 fork, for example)

- Boot the machine normally

- Complete the Setup Assistant first user creation process, setting a password

- Reboot into Recovery

- Open the Secure Startup Utility and allow booting from external media and either

- Set it to No Security, or

- Leave it at Full / Medium (may require network connectivity to Apple, more on this below)

- Reboot to the external media

- NOW you can begin your workflow

… Not exactly “light touch” anymore, is it?

But let’s go over why this is. Let’s talk about what Secure Boot requires of your machine.

[ Note: This blog post doesn’t cover every aspect of what Secure Boot is checking or doing, but it does cover some new useful technical details. - mike ]

Let’s talk security levels

No Security

I’m putting this one first because it’s the easiest to talk about. Simply put, this is closest to the classic boot model we knew before the T2. All the normal stuff applies.

The device firmware has to be able to see a boot.efi it can use in a volume it can read and boot from and the OS inside the volume has to say it supports the hardware (which is foremost stored in /System/Library/CoreServices/PlatformSupport.plist, if you’ve ever wondered) and provide all the necessary hardware kexts for talking to the bits of the computer.

Secure Boot devices come with additional requirements in that the T2 chip runs its own OS (bridgeOS), but yadda yadda yadda this isn’t the boot mode you’re interested in reading about. This is your normal “if the OS is compatible, it can boot the Mac” situation.

Full Security

What’s different about this mode? Let’s investigate.

We’ll ask a Secure Boot device what it’s booting. Let’s start with the bless command:

sudo bless --getBoot --verbose

There’s a lot of information there.

But if you’ve never noticed this before on macOS devices that boot APFS (like all Secure Boot devices), macOS isn’t booting a file off of the System volume (/dev/disk1s1), it’s booting the boot.efi file from the new APFS Preboot volume (/dev/disk1s2) that you’ll find inside APFS containers:

<key>BLLastBSDName</key>

<string>disk1s2</string>

<key>Path</key>

<string>\FD77CA06-84E9-42D0-B5FE-6295D28CBB2F\System\Library\CoreServices\boot.efi</string>

It doesn’t matter if you’ve encrypted the device or not. Every macOS device booting an APFS filesystem boots like this.

You can see the container layout with this command: diskutil apfs list

It comes in a triplet: OS/System volume, Preboot, and Recovery. If you’re booted from a System volume within an APFS Container, you’ll also see a (temporary) VM volume, which has taken the place of and is mounted at /private/var/vm.

So we’re booting from Preboot.

Since we’re trying to figure out what’s different about a Secure Boot device, does the Preboot volume of an older Mac without a T2 chip look different in comparison?

Let’s mount them and see. For the OS that’s booted off the internal disk, that’s usually:

diskutil mount /dev/disk1s2

It should mount at /Volumes/Preboot

If you look at the top level of the disk, you’ll see one (or more) folders that look like long hex strings with dashes in them. Those are GUIDs. Not only are they GUIDs, but the GUIDs match some of the output that we saw before in diskutil apfs list

A System volume within an APFS Container has its own unique GUID. Within Preboot (and the Recovery volume as well), the top level folders will contain a folder with a name matching the GUID of the System volume it’s paired with.

+-> Volume disk1s1 FD77CA06-84E9-42D0-B5FE-6295D28CBB2F

| ---------------------------------------------------

| APFS Volume Disk (Role): disk1s1 (No specific role)

| Name: Macintosh HD (Case-insensitive)

| Mount Point: /

ls -l /Volumes/Preboot/

total 0

drwxr-xr-x 7 root wheel 224 Jul 17 09:38 FD77CA06-84E9-42D0-B5FE-6295D28CBB2F

In the HFS+ boot model, the kernel is hardcoded to look for the Recovery partition at the partition id minus 1 of the associated System partition. With APFS, a single APFS container can now contain multiple System volumes - but only a single Recovery/Preboot volume is required within the container, each of which can contain multiple GUID-named folders (one for each System volume).

Looking back at the information we got from the bless command, we can see that the boot.efi is in a subfolder within the GUID folder: System/Library/CoreServices/boot.efi

<key>Path</key>

<string>\FD77CA06-84E9-42D0-B5FE-6295D28CBB2F\System\Library\CoreServices\boot.efi</string>

So, if this is the boot target of the Secure Boot device, maybe there’s something in here related to the Secure Boot process.

There’s quite a few files in the Preboot volume.

Maybe we could compare them to a device running the same OS version without a T2 chip. For the record here, that means I’m comparing an iMac Pro to a 2017 MacBook Pro running 10.13.6.

Let’s chop out the GUID names at the beginning (since they’re unique to every System volume) and just compare the contents of the subdirectories. Sort the lines of each and run both of them against each other through the diff command:

*** Standard-listing.txt

--- SecureBoot-listing.txt

***************

*** 4,12 ****

--- 4,15 ----

com.apple.installer/.disk_label_2x

com.apple.installer/boot.efi

+ com.apple.installer/boot.efi.j137ap.15156C1879A0A6.im4m

com.apple.installer/boot.efi.j137ap.im4m

+ com.apple.installer/bootbase.efi.j137ap.15156C1879A0A6.im4m

com.apple.installer/bootbase.efi.j137ap.im4m

com.apple.installer/BridgeVersion.bin

com.apple.installer/BridgeVersion.plist

com.apple.installer/com.apple.Boot.plist

+ com.apple.installer/immutablekernel.j137ap.15156C1879A0A6.im4m

com.apple.installer/PlatformSupport.plist

com.apple.installer/SystemVersion.plist

***************

*** 38,41 ****

--- 41,45 ----

System/Library/CoreServices/.root_uuid

System/Library/CoreServices/boot.efi

+ System/Library/CoreServices/boot.efi.j137ap.15156C1879A0A6.im4m

System/Library/CoreServices/boot.efi.j137ap.im4m

System/Library/CoreServices/bootbase.efi.j137ap.im4m

Wow. The only different files are on the Secure Boot device.

im4m files - what are those?

Google has some interesting hits: IMG4 File Format

A “manifest” file. A structured tag file that contains signatures for OS components. Used on some of Apple’s other OSes, including iOS.

Let’s go back to Apple’s description of what Full Security does:

During startup, your Mac verifies the integrity of the operating system (OS) on your startup disk to make sure that it’s legitimate.

That sounds like something signatures would be useful for.

This information is unique to your Mac, and it ensures that your Mac starts up from an OS that is trusted by Apple.

Oh? So this might be different if we look at yet another iMac Pro? Good thing I access to a few to compare 😄

And sure enough, there are the same additional files on the other device, but the hex string before the .im4m suffix (the 15156C1879A0A6 in boot.efi.j137ap.15156C1879A0A6.im4m) is different.

Well.

If we think this is part of the security signature, let’s start with some basic experimentation and just rename (just in case we need it again …) these files.

[ Note: I had to do it from Target Disk mode! Some fun filesystem protections here (if you want to play at home) - mike ]

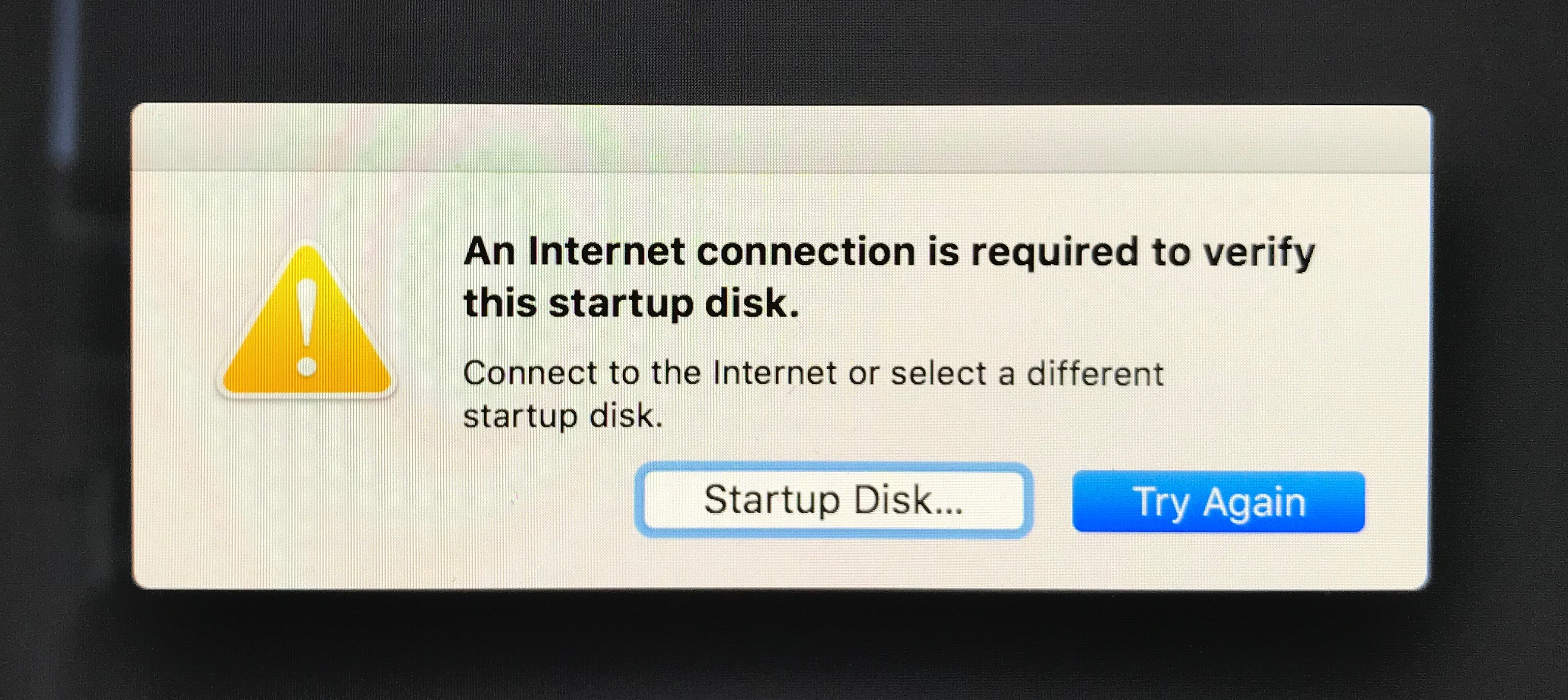

For extra grins, let’s poke at this comment and make sure the network is disconnected before reboot:

If your Mac can’t connect to the Internet, it displays an alert that an Internet connection is required.

Annnnnnd ……. ?

BINGO. It would seem we have part of the equation.

Reconnecting the device to the network and then later checking in Preboot, it would seem new *.j137ap.15156C1879A0A6.im4m files have been recreated.

Interestingly, each one rebuilds a uniquely named file - but always with the same hex name for itself.

They appear to be different every time they’re remade because the checksums keep changing. So they’re not static records but instead are likely dynamic signatures, needing that network access in order to be created.

So maybe the static hex string is a unique identifier of sorts.

We should try searching the machine for the identifier - maybe we can find out what it is.

Normally for this kind of thing, if I want to search through the entire contents of the machine I’d reach out to my standard tools like the Silver Searcher or RipGrep. Both of these tools will gladly recursively search through both text and binary files to locate strings you’re interested in. These guys get frequent shoutouts in my reverse engineering talks.

However, in this case, I dumbly lucked out by trying the naive approach and checking to see if the output of system_profiler (which lists other unique identifiers like ethernet MAC addresses, serial numbers, etc.) happened to contain the hex string in question.

It did!

But only because I’d freshly re-installed the OS and system_profiler tends to include recent portions of several log files. In this instance, it included install.log:

ApECID? There’s also an ApBoardID. So maybe that’s just EC? Or ECID?

Let’s try our good friends at the iPhone Wiki again, maybe they know.

The ECID (possibly standing for Exclusive Chip ID or Electronic Chip ID) is an identifier unique to every unit.

There’s a ton of detail on that page. It’s most likely lots of educated guesses from non-Apple people. Likely not all of it applies to Secure Boot Macs. But if you play around with some of the tools and suggestions they have, you’ll find out that we’re looking at basically the same thing.

Growing evidence of the new process

So Secure Boot Macs have a new unique identifier which iOS devices have had for some time: the ECID.

And it would appear that a signature manifest is generated as part of the Secure Boot process that, in Full Mode, makes a signature specific to the ECID of the device itself.

… are there any other good tidbits in the log near there?

WHOA!

So we now know this entire new process is called “personalization” AND we know the URL that it’s reaching out to: http://gs.apple.com:80/TSS/controller?action=2

Any more friendly hits on the wiki for that site or URL?

Wow, the “Sending data (request)” section there looks very similar to the details the Mac is sending: @HostPlatformInfo, ApECID, etc.

This is locking it in pretty solid that Apple has leveraged this same technology for generating signatures for validated booting for Secure Boot on Mac.

Knowing what we know now, we can play a little bit more to help confirm these files are unique to the devices they’re generated for.

Copying them between Secure Boot devices and renaming them to match the ECID of the other device still results in Secure Boot wanting to repair the signature.

Going back to the 2017 MacBook Pro that does not have Secure Boot, it doesn’t have a uniquely named .im4m file - but it does have a “generic” .im4m file for the boot.efi: boot.efi.j137ap.im4m

What happens if we delete it?

… Still boots.

So apparently devices that are not Secure Boot don’t rely on (or check/validate) the .im4m files during the boot process at all.

Let’s take one last bit from the logs that helps to confirm that these signatures are indeed the .im4m files:

Pretty clear proof that the result of the personalization process is saved to these .im4m file paths.

But what about ..

Medium Security

Allows any version of signed operating system software ever trusted by Apple to run.

During startup when Medium Security is turned on, your Mac verifies the OS on your startup disk only by making sure that it has been properly signed by Apple […]

No mention of “This information is unique to your Mac”.

So let’s:

- Set it to Medium

- Delete those uniquely named .im4m files again, then

- Reboot!

… Hmmmmmmm, it booted.

Now my directory structure is an exact match for the 2017 MacBook Pro. I no longer have .im4m files with the ECID hex identifier.

But what about these other .im4m files that are in there (the ones without the ECID names in them)?

Maybe that’s what we’re relying on now?

Deleting .im4m files - ROUND 2!

And as soon as you do that, yes, you run into alert dialogs that the OS is no longer trusted or bootable and needs repair.

Let’s expand the thought process again.

Because there was no statement that “This information is unique to your Mac” … could we copy them from the 2017 MacBook Pro (which doesn’t have Secure Boot) back to the iMac Pro (which does have Secure Boot) and get the iMac Pro booting again?

Answer: YES

Repeating the experiment but this time copying .im4m files from a machine running 10.13.5, we get blocked at boot again.

So we now know the “generic” .im4m files are OS specific.

Knowing what we’ve found so far, let’s loop back and look at these .im4m files again and the wiki page we found mentioning them. There’s some interesting notes at the bottom mentioning ASN.1.

Are .im4m files just simply ASN.1 encoded?

Let’s run them against openssl asn1parse and find out:

boot.efi.j137ap.15156C1879A0A6.im4m:

boot.efi.j137ap.im4m:

Cool details!

There’s an embedded x509 cert in there, coming from “Apple X86 Secure Boot Root CA - G1” and “T8012Mac-TssLive-ManifestKeyGlobal-RevB-DataCenter”, for validating the signature.

And there’s a lot of those 4 letter fields: BORD, CHIP, etc.

Each of those is probably related to one of the attributes like we saw being supplied in the install.log to the personalization service.

What’s very interesting is that the ECID field is very definitely present in the Full Security mode manifest, but is missing in the Medium Security manifest. Yet again more confirmation that they’re not tied to specific hardware.

This would seem to imply that unlike Full Security mode, in Medium Security mode you could simply place already generated and correct .im4m manifests on disk - without access to the internet - as no device-specific personalization needs to occur.

One complete set of .im4m signature files is good for that OS on whatever hardware it’s compatible with.

(The phrase “air gapped imaging” comes to mind …)

And now that I’ve mentioned it - let’s talk about all of this in the context of imaging.

The lifespan of imaging: not as dead as we thought, yet

Some of us in the community have spoken quite well about it already:

- Imaging is Dead: Now What? (by the masterful Greg Neagle)

- Imaging will be dead soonish (by the Blogfather himself, Rich Trouton)

In the early first release days of the iMac Pro, there was talk that you couldn’t use asr to restore an OS image to the device and have it boot out of the box.

However, if you were fortunate enough to have two iMac Pros (or brave enough to try from Internet Recovery), they could apparently image themselves.

Did you bother to check back after this news? Have you tried it again recently?

If you’re making a never booted image with wonderful tools like AutoDMG, these days asr can very definitely restore a booting macOS onto these devices, even if the host device running the asr restore is not a Secure Boot device.

So what changed?

When the iMac Pro came out, it was running a special fork (not uncommon for new hardware builds) of the current OS at the time: macOS 10.13.3 build 17D2047

When 10.13.4 was released, it was a unified build and the iMac Pro no longer ran its own fork.

So, using the knowledge of “personalization” above, can we look at the asr command itself and see what may have changed?

Let’s try some of my most favorite (and built-in) tooling to peek at the binary - strings and otool:

strings /usr/sbin/asr | grep -i personaliz

no-personalization

Couldn't personalize volume %s

Personalization failed with error %d, line %d

no-personalize

personalizationRequiredForVolumeAtMountPoint:

networkAvailableForPersonalizationWithOptions:

personalizeVolumeAtMountPointForInstall:outputDirectory:options:completionHandler:

otool -L /usr/sbin/asr | grep -i personaliz

/System/Library/PrivateFrameworks/OSPersonalization.framework/Versions/A/OSPersonalization (compatibility version 1.0.0, current version 48.1.0)

It would appear asr gained a new trick!

In fact, the asr in the iMac Pro’s copy of 10.13.3 already had this new capability, which is why it worked from device to device or from within Recovery to itself.

asr on any 10.13.4+ macOS version now has the same capability without the need for special undocumented flags or tricks.

If you tinker a little deeper (like I have), you’ll find out that there’s code in the OSPersonalization PrivateFramework to read the ECID of a target disk mode attached device. This allows it to personalize a device even in Full Security mode with the ECID-specific, device-specific manifest.

The Million Dollar Question

So. Should you image?

Apple tells you blatantly: NO

How to install macOS at your organization

Apple doesn’t recommend or support monolithic system imaging as an installation method, because the system image might not include model-specific information such as firmware updates.

Or do they? Read it again.

Apple doesn’t recommend or support

They don’t say you can’t. Just that they don’t recommend it. That it’s not supported.

They quite obviously built the functionality into asr.

But - should you?

It’s hard to beat the speed of target disk mode restore of an AutoDMG built image.

And Secure Boot devices support Target Disk mode out of the box. This means you can restore a personalized image to a Secure Boot device and it will boot it first try. Suddenly a “light touch” (hold T at boot) workflow is back. And there are amazing tools starting to be available out there for this like Google’s Restor.

But - should you?

Are you someone that needs to worry that a delivered device has been manipulated mid-shipment?

If you try placing a simple LaunchDaemon on a Secure Boot device’s System volume, it doesn’t stop it from booting in Full Security mode. That’s not one of the things in the signature manifest. Honestly there are a billion places the OS could be modified to auto-launch things as root at start up. Secure Boot checks some things. It doesn’t check all things (yet?). It’s focused right now on securing the core of the boot process.

So what do you do in that situation instead? Internet Recovery?

Guess how many machines you could have restored back to vanilla with something like Restor in the same amount of time.

But - should you?

because the system image might not include model-specific information such as firmware updates

This warning is something to consider. There have been definite changes in how the OS installer works. If you were going to do image restoring workflows, you should consider that portions of your device may not have the necessary software if you’re restoring anything other than the last OS version it ran. To make this effective, you’d probably need to keep your fleet of devices on top of OS updates and make sure your restoration image is the latest OS version with patches at all times.

But - should you?

There are also alternative projects out there that are more than “light touch” but still drastically less than running through Setup Assistant just to create an account you’ll destroy again. An example of this is Greg Neagle’s Bootstrappr.

Boot into recovery, type two commands, and you’re off to the races.

But this only works for provisioning clean machines. If you’re bringing devices back from users to be redeployed, it won’t wipe and restore the machines to a pristine state or deal with FileVault encrypted disks, etc. So you’re still looking at something like Internet Recovery to return the device to a new state.

But - should you?

Secure Boot macOS devices are still very new! There are definitely corners and edges around the concept of imaging them that we surely haven’t stumbled over yet.

But - should you?

Apple doesn’t recommend or support

I think if you read between the lines there, Apple understands that right now some organizations may feel they have the need for these workflows still.

If Apple continues down similar paths to what it’s done with iOS, they could eventually possibly split the OS into its own volume - possibly even in a read only image with all mutable and user data stored separately.

If they ever get to that state, some of the security concerns above will just evaporate. The only OS on the device will be one that’s trusted and verified to a deeper state than macOS is today. We could even gain the “Erase All Content And Settings” functionality.

Nobody but Apple knows will be next. But they do, in the meantime, provide guidance.

And their guidance is that you should be looking at DEP/MDM-based workflows for your provisioning. The latest operating system versions already include some features (like managing automatic kernel extension loading) that can only be done remotely and adjusted post-deployment via MDM deployed profiles. SIU had the capability to make network bootable images that ran scutil to reconfigure the trust settings, but all of that is moot now that Secure Boot devices don’t network boot at all. MDM is the only game.

If you or your organization feel the need to image devices, then do so.

Just know why you’re doing it. Simply putting files on disk isn’t a good enough reason. MDM or MDM-deployed agents can do that.

And be aware it is very very very likely not a long term solution.

You should definitely, in the meantime, be getting MDM going in your environment.

As always, hope this helps.

- mike

postscript -

With access to the 2018 MacBook Pro, if you look at the Preboot volume, you’ll see two different but similar files for its version of macOS.

Instead of just the “j137ap” .im4m files, you’ll also see “j680ap” and “j132ap” files.

Going back to the install.log again, you can find this line:

HardwareModel = j137ap;

Quick Google searches will suggest that “j137ap” is likely an internal model identifier of either the iMac Pro itself or the specific T2 chip inside it. “j680ap” and “j132ap”, with a little poking around, you’ll find are for the new 13” and 15” 2018 MacBook Pro devices.

This would indicate that the signatures, while “generic” in Medium mode, do still need to exist for the specific Secure Boot device model you’re attempting to boot it on.